Kuhmo is not only known for its music festivals but was also named a UNESCO City of Literature in 2019. This award recognises the Finnish city's commitment to the Finnish national epic poem Kalevala. Olga Zaitseva is the director of Juminkeko, the central cultural and information centre for Kalevala and Karelian culture in Kuhmo. The 45-year-old was born in Russia. Her mother tongue is Vepsian, as she belongs to the Vepsian minority, a Finno-Ugric ethnic group that is mainly at home in Karelia, but also in the Leningrad and Vologda oblasts in north-west Russia. The language is similar to Finnish, Estonian and Karelian. Olga says that she grew up knowing that although Russian is her official citizenship, her identity and nationality is Vepsian. "Even as a child, I attended Vepsian courses in addition to Russian-language school. It was the time of perestroika, when we Veps rediscovered our culture and identity. I always felt positive about being part of a small minority and was therefore always proud of our language and culture." She was strongly influenced by her parents. "My mum also spoke Vepsian language as a child, but she didn't even have a name for it. It was only later that she realised the richness of the language, so she completed a doctorate in Vepsian and translated the Kalevala and the New Testament into Veps language.

Olga left Russia with her family in 2009. The reason was studying. She and her husband attended courses at the University of the Nations and studied Bible in Norway and Finland. “In Russia I could only work as a as a technical translator at a nuclear power plant after studying Finnish and Vepsian. It was a good, high paid job. But not everything is measured with money.”

2013 to 2014 was a stroke of luck for Olga, as she was able to work as the coordinator of an EU-funded project in Kuhmo. The project aimed at founding ethno-cultural centres which would represent indigenous groups. The prerequisite was language skills in various languages such as Karelian, Vepsian, Russian, English and Finnish. ‘I could do all that.’ A few years later, in 2018, she became head of Juminkeko.

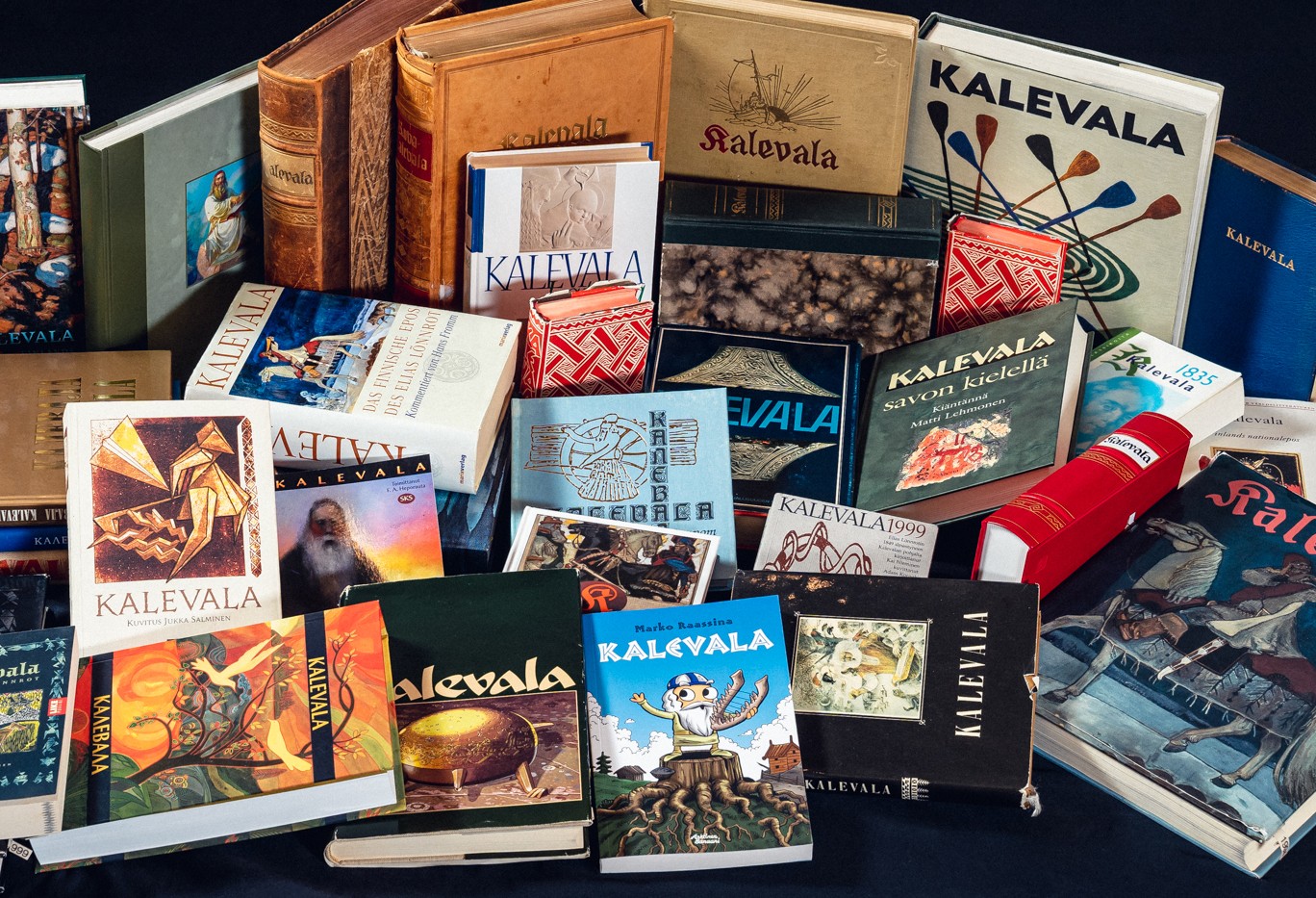

Olga describes her main task as follows: ‘To maintain, popularize, cherish and keep accessible the cultural tradition associated with the Finnish national epic Kalevala.’ Kuhmo has one of the world's largest collections of Kalevala editions, which can be used by anyone. Olga points to the various translations and editions of this work in a display case. The Finnish national epic has been translated into 60 languages. There are also abridged versions, versions for school lessons and editions for children.

The ‘Kalevala’ has great cultural and historical significance for Finland. It made a decisive contribution to the Finnish national consciousness. "Finland was under Swedish and Russian rule for centuries. Finnish only existed as a spoken language," explains Olga. The Finnish language professor and physician Elias Lönnrot collected oral folk songs and poems while travelling through the villages for decades. He was particularly successful in Karelia, a region that is now divided by the Finnish-Russian border. The population of the remote villages possessed a particularly large treasure trove of traditional spells and myths that had developed over thousands of years.

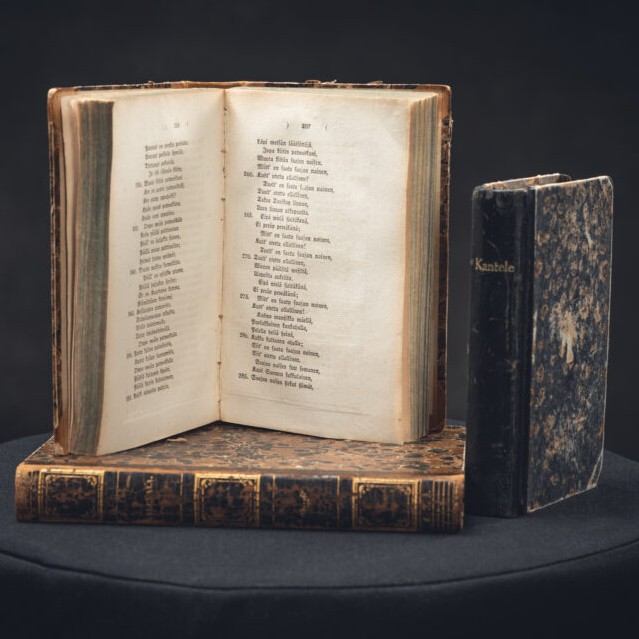

‘He had so much material that he could have published several books,’ explains Olga. ‘He created connections between the individual texts and wove them into this huge epic.’ The first version was published in 1835, the second in 1849: ‘This is the version we know and use today.’

‘Finnish identity is based on the Kalevala and the folk songs and poems of Karelia,’ explains Olga. A large part of this historical landscape is now in Russia. This means that the origins of the Kalevala also lie partly in Russia. ‘In recent years, we have cultivated intensive contacts with Russia in order to preserve and research this shared cultural heritage.’ Olga raves about concerts in Russia and Finland where the old songs, which are typically accompanied by the kantele, could be heard. The kantele is a fretless box zither that is considered a magical instrument in the Kalevala.

Olga is able to bring her Vepsi background to bear in her work for the Juminkeko. ‘On the one hand, there are many connections between Karelian and Vepsian culture, and on the other, it is also part of the cultural centre's remit to look after various ethnic groups and minorities.’ The Vepsians are one of them.

A total of 5,000 people in Russia officially identify as Vepsian. ‘I assume that there are even more, but many no longer dare to call themselves such in today's Russia.’ There are no figures for Finland. Through her work, she from Juminkeko in Finland is making a decisive contribution to preserving the language and culture of a Russian minority.