Porkkala is a peninsula on the south coast of Finland. The typical archipelago landscape with rocky coasts and offshore islands is only an hour's drive from Helsinki and is a popular destination for excursions. Hiking trails and nature paths criss-cross the peninsula. Shelters and fireplaces invite you to linger and offer wonderful views of the sea.

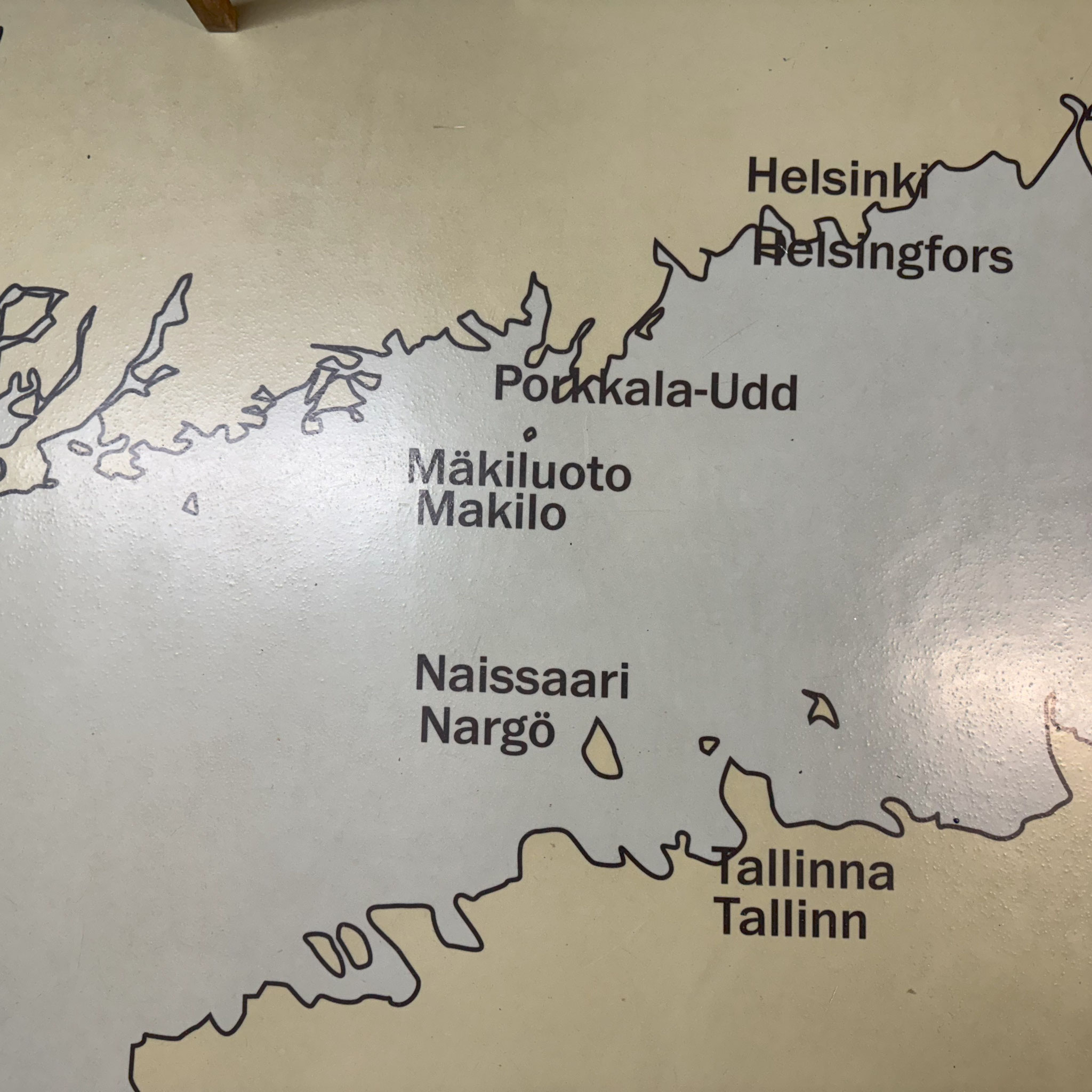

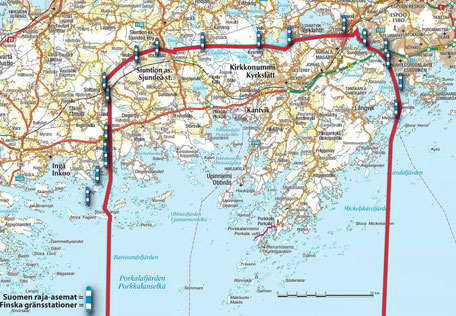

Porkkala also has a completely different history. In the Moscow Armistice Agreement of 1944, Finland had to lease an area of 380 square kilometers to the Soviet Union for 50 years. This included the Porkkala peninsula and the neighboring communities to the north. The reason for this was that it is the narrowest and shallowest point in the Gulf of Finland. The Estonian coast is only 36 kilometers away. The Soviet Union established a military base here close to the Finnish capital.

For Finland, this was a tough condition for the armistice and at the same time a threat to independence. 7,200 Finnish inhabitants and 8,000 head of cattle had to be evacuated within ten days. The families of Berndt Gottberg and Lena Selèn were also affected.

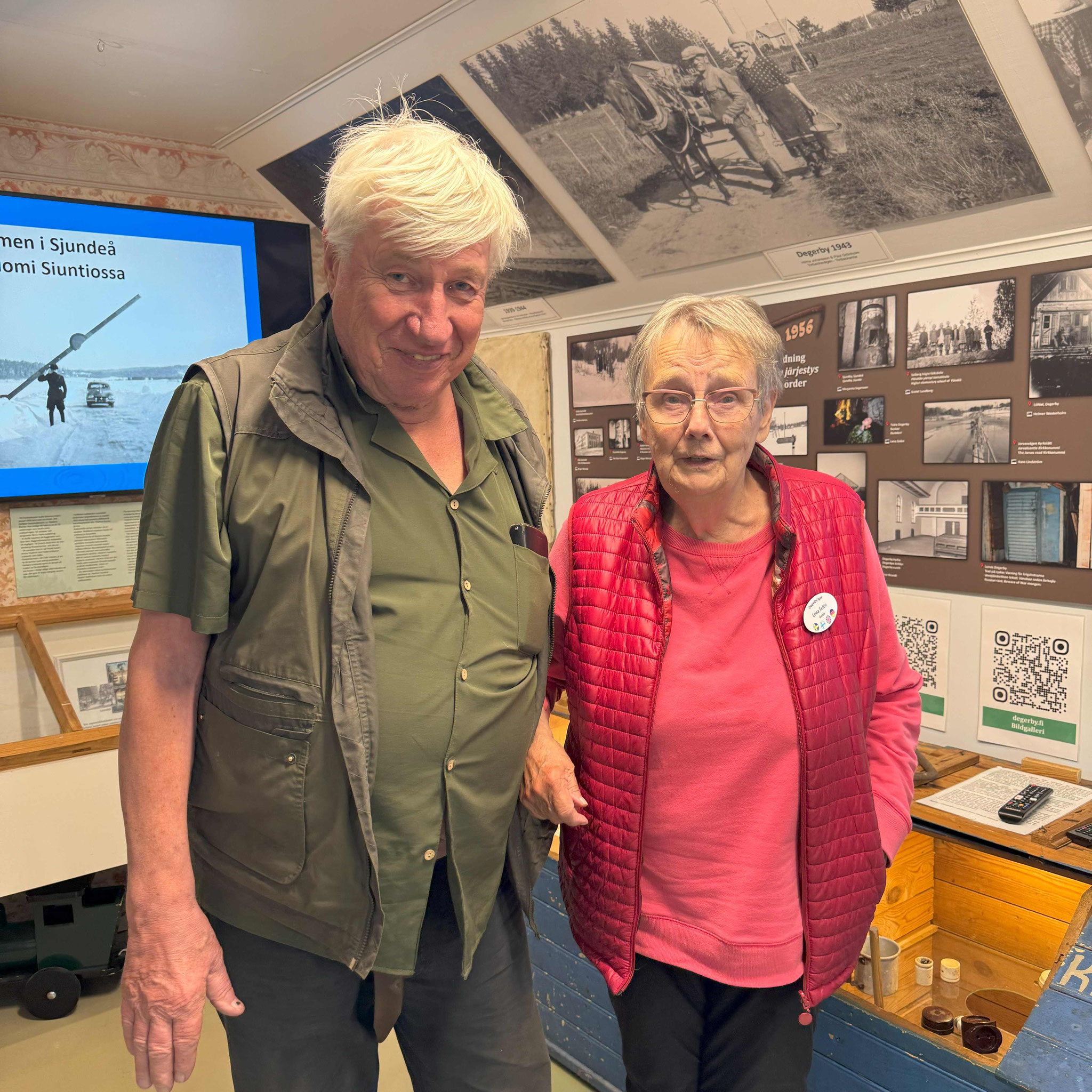

Lena, born in 1941, tells us today in the museum in Degerby that she actually lived in Helsinki. "But because of the bombing during the war, I lived with my grandparents in Degerby. The small community was located in the area that had to be leased to the Soviet Union."

Berndt Gottberg's mother, born in 1949, ran a farm in the area occupied by the Soviets. The family moved to Inkoo, about 20 kilometers away. Bernd spent his early years there while his mother worked as a teacher at the agricultural school.

“There were an estimated 20,000 soldiers and 10,000 civilians living on the military base,” says Lena. "No Finns were allowed to enter the area. There was a fence around the military area and even a border strip that was always harrowed to detect any footprints." There were also attempts to escape from Soviet territory to Finland. “However, according to the treaty, any fugitives had to be handed over to the Soviet Union,” explains Berndt. The people at the military base were primarily supplied and transported to and from the base by ship and train. "But there were also Russian cars traveling between the Soviet Union and Porkkala. They were not allowed to be stopped by the Finnish authorities." The railroad line from Helsinki to Turku ran through the “leased area”. At first, Finnish trains were no longer allowed to run. After long negotiations, this important rail connection was made possible again. However, Soviet locomotives had to be used and the doors were locked and the windows closed. It was called the “longest tunnel in Finland”. It was 41 kilometers long.

Porkkala had to be leased to the Soviet Union for 50 years, i.e. until 1994. “Most of the people who were evacuated from the region in 1944 never expected to be able to return home,” explains Lena.

But then came the surprise: after just eleven years and four months, on January 26, 1956, the Soviet Union returned the entire area to Finland. There were many reasons for this: maintaining the military base was too expensive, there were other military options and Stalin's successor Nikita Khrushchev pursued a policy of “peaceful coexistence”. The return of Porkkala was intended as a gesture of goodwill.

The Finnish state decided that the people could return to their homes. “But everything was destroyed and broken and had to be rebuilt first,” says Berndt. Around 80 percent of them returned. "My parents also decided to rebuild their house and farm their land again. We then returned in 1960." Lena shows a photo of herself and her mother from 1956, sitting on the spot where their house once stood. “Nothing is left of our house except the base of the tiled stove.” Lena says that she hated Porkkala as a teenager. "What was I supposed to do there? Everything was broken and I had no relationship with the place. My childhood paradise was in the place where my grandmother lived after the evacuation." Lena worked as a journalist in different places in Finland. She only returned in 1988, to look after her grandmother's house.

“That's when I started to look into the history,” says Lena. She met her current husband Berndt, and they have both been researching the Porkkala story ever since. Lena has conducted around 200 interviews with people who had to leave the area. Together they have published five books and documented everything from that time. The village association runs the “Degerby Igor museum”. “We were both involved in setting it up from the very beginning,” explains Lena. “People from all over the world come here to find out more.”

Berndt also talks about German prisoners of war at the Soviet military base in Finland. “We don't have any official documents about it, but we have lots of clues.” Lena reports on buttons with the words “Kriegsmarine” on them that were found, as well as writing such as “Auf Wiedersehen” on walls. Not only the Russian Orthodox cross, but also the Latin cross was found on the bunker remains. There are also letters from German prisoners of war from Porkkala, which are archived at the Red Cross. Berndt reports on some buildings that were erected so neatly that only the Germans are credited with this. “The Russians just did a sloppy job, so you can see the difference.”

Lena and Berndt explain why the museum in Degerby is called ‘Igor’: During the war, around 90 prisoners of war worked on farms in Degerby. There was a shortage of labour, as many Finnish men were still at war or had been killed in action. The living conditions on the farms were better for the prisoners than in the camps. Igor was a Ukrainian prisoner who gave a little Finnish girl a wooden doll he had carved himself as a farewell gift. ‘This doll is now in the museum,’ says Lena. ‘We also want our museum to promote understanding between people, which is why we named the museum ’Igor" as a symbol of friendship. Due to the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, this is not always easy, especially as it is known that Stalin sent many Ukrainian soldiers to the war against Finland. They were poorly equipped and had no interest in fighting against an independent Finland."

Lena says that Russians also visited the museum. “They wanted to get to know their children's paradise,” she explains sympathetically. It is not known how many Soviet children were actually born in Porkkala in Finland during the eleven years. But we do know that it wasn't just a heavily guarded base. Not only were there bunkers, tank roads, a naval port and an airstrip, but Porkkala was also a Russian town with schools, kindergartens, hospitals, cinemas and restaurants.

Lena is keen to tell this story to everyone, and she is very understanding of the fact that Russians also visited this place. In view of the closed border with Russia, she says: "We have to learn to be friends." She doesn't know when this will become a reality, “but I have hope that things will get better at some point.”

Map: Degerby Igor Museum

Black and white photo: Lena Selèn and her mother Gudrun Broström in spring 1956 at the remains of their house in Degerby after the withdrawal of the Soviet army; photo: Jemima Moliis

All other photos: Beatrix Flatt