Lenin's Head on the Missile Base

From 1961 to 1989, there was a Soviet nuclear missile base in Zeltini in north-east Estonia with four launch pads for medium-range ballistic missiles. Their range was given as over 2000 kilometres. They could therefore have reached many important European capitals. Fortunately, these weapons were never used. It was the Cold War and around 300 military personnel spent 38 years here preparing for a possible emergency.

Gunita Paleja has lived her entire life near this top-secret facility. After the Soviet army finally left the site in 1991, she began researching and conducted interviews with people who had worked there. ‘It was difficult at first because many former officers didn't want to talk.’ After all, they had worked in the utmost secrecy over the last few decades. But Gunita didn't let up. ‘I kept talking to people and found out more and more details.’ Today, she gives guided tours of the 20-hectare site and can explain in detail how this former Soviet nuclear missile base works.

Nobody in the region knew what was happening here. ‘There were no locals working here either, but specially trained experts from all over the Soviet Union,’ explains Gunita. At most, locals worked in the kitchen or as housekeepers, secretaries or laundry workers. There were soldiers who lived and worked on the compound all the time. Officers and managers always had two-week shifts in which they lived on the military grounds. During their free time, they lived a normal life, had flats in the nearby town of Alüksne, for example, got married, started families and took part in social life. ‘They were very respected people, considered interesting and intelligent,’ summarises Gunita. "High-ranking members of the army went hunting with men from Alüksne. So they knew each other," says Gunita, describing the situation. "Today, you could say that the officers who worked here led a kind of double life. Because nothing got out. Nobody knew that they were part of the Soviet nuclear programme and that they trained every day to fire nuclear missiles towards the West."

However, Gunita is also keen to emphasise that the region also benefited from this military facility. For example, roads were expanded and new apartment blocks were built. Sometimes the soldiers also helped with heavy agricultural work.

"The population knew nothing about nuclear weapons. It was also not the time for the population to ask critical questions," says Gunita. However, the topic of radioactivity was a recurring theme among the population. ‘But it was all just speculation, as there was no official information.’ She tells of an officer who recommended to a good friend that his pregnant wife should leave the area for a while. ‘It would be better for her health,’ was the reason given. ‘And I was also pregnant at the time,’ says Gunita. ‘And I didn't know anything about radioactive radiation at the time.’ However, she remembers a situation around the birth of her child when a doctor asked her where she lived. He reacted with some concern when he heard Zeltini. ‘But everything went well,’ she says today. Investigations by an international authority in 1991 confirmed that there was no increased radiation exposure on the site.

The former military site is now a mixture of a military-historical sight, an industrial estate and a huge “lost place”. Gunita explains that the site was subject to vandalism after the withdrawal of the Soviet army. People were mainly looking for metal as a valuable raw material. People were mainly looking for metal as a valuable raw material. "All the pipes and cables were removed. The entire electrical system, water supply and heat supply were destroyed." What remained were primarily concrete buildings, hangers for storing the missiles and missile warheads, the command centre and bomb shelters.

The entire site was monitored, sealed off from the public and top secret. Gunita explains that the area where the nuclear warheads were used for work and training was specially secured. She knows from eyewitness accounts that the area was surrounded by a deadly electric fence. There is one documented case in which a soldier died on this fence. Only the best and most qualified officers were allowed to work in this area. However, it was not only their expertise that was enough, these people were also vetted by the Soviet secret service ‘KGB’. They wore special protective clothing for this dangerous work. Radioactivity was constantly measured.

In the command centre, it was all about pressing the button in an emergency. A former officer reports that there was no critical reflection after the order. It was also not a red button, as is often assumed, but there were two buttons that had to be pressed simultaneously. There were still two other people in the room to ensure that the buttons were pressed in any case. According to Gunita, not carrying out the order was unthinkable.

So that the officers could get to safety in an emergency, there were several underground bunkers with different equipment; two with very different equipment have been preserved. One was equipped for a longer stay, the other only for a short time.

Fortunately, only the worst-case scenario was rehearsed in Zeltini. It never materialised. Today, Gunita regularly organises guided tours for groups and school classes. There is an audio guide available so that interested people can discover the site on their own. It is used for motorsport, and every now and then there is a music festival in one of the hangars. ‘But the most important thing is that this site is preserved as a military-historical sight so that people understand that the Cold War really existed,’ says Gunita. ‘The city of Alüksne is now responsible for the site,’ explains Liva Bulina from the city's tourism department. ‘Gunita's work is of incredible value to us.’

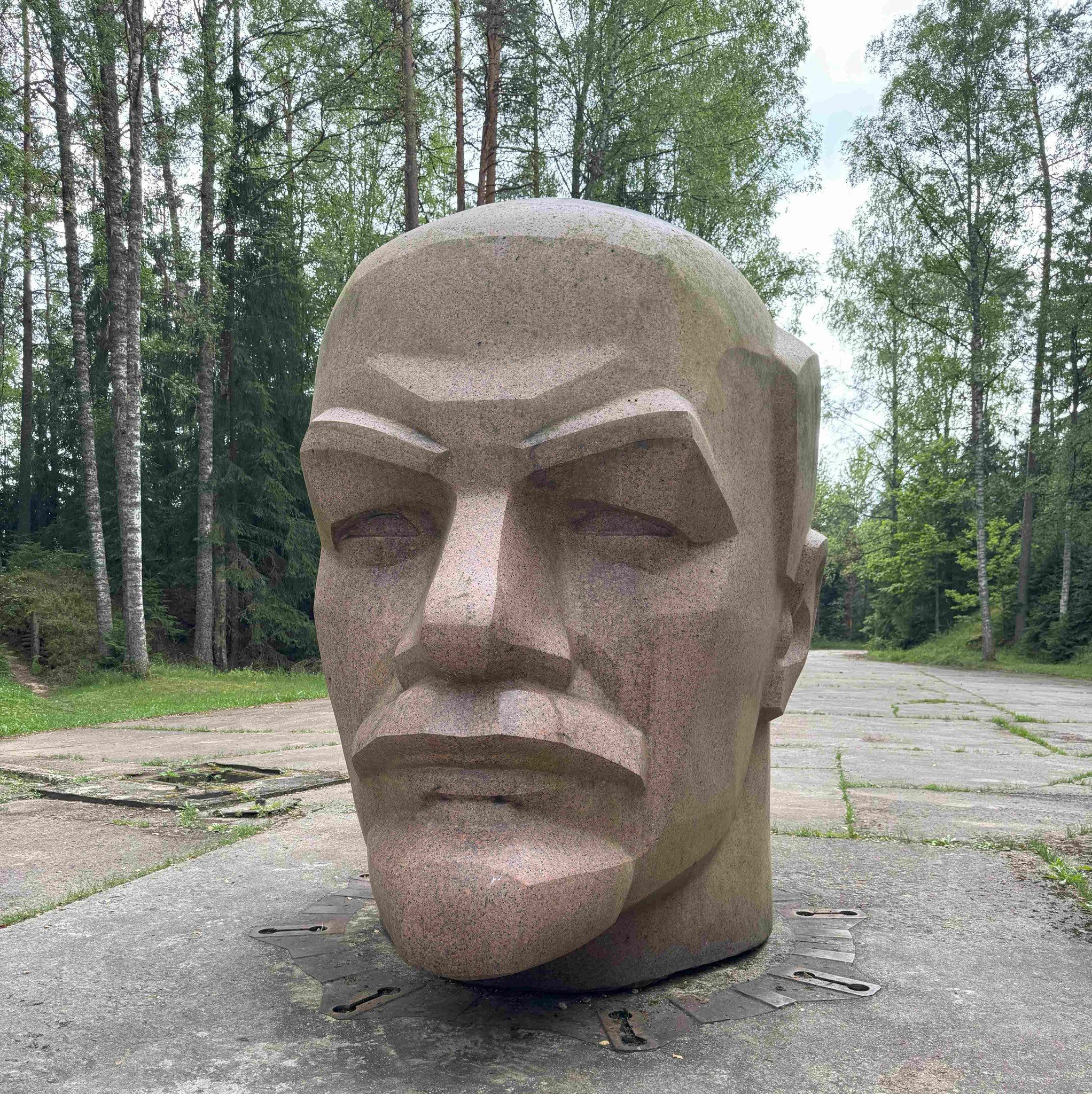

The Lenin head, which stood in the centre of Alüksne until the 1990s, has found a new home. At 3.5 metres high, it is one of the tallest in Europe. It now stands in the centre of the former launch pad for medium-range weapons with nuclear warheads.