Josifs Ročko was born in 1948 as a Jew in Daugavpils, eastern Latvia. His father was one of the few survivors of the Daugavpils Ghetto. His mother emigrated to Russia and returned to her hometown after the war. His father lost his entire family during the Holocaust; all were shot.

Fifteen years ago, Josifs Ročko began to research the history of Jews in Daugavpils and Latgale. He has published several books and established a museum on the first floor of the synagogue.

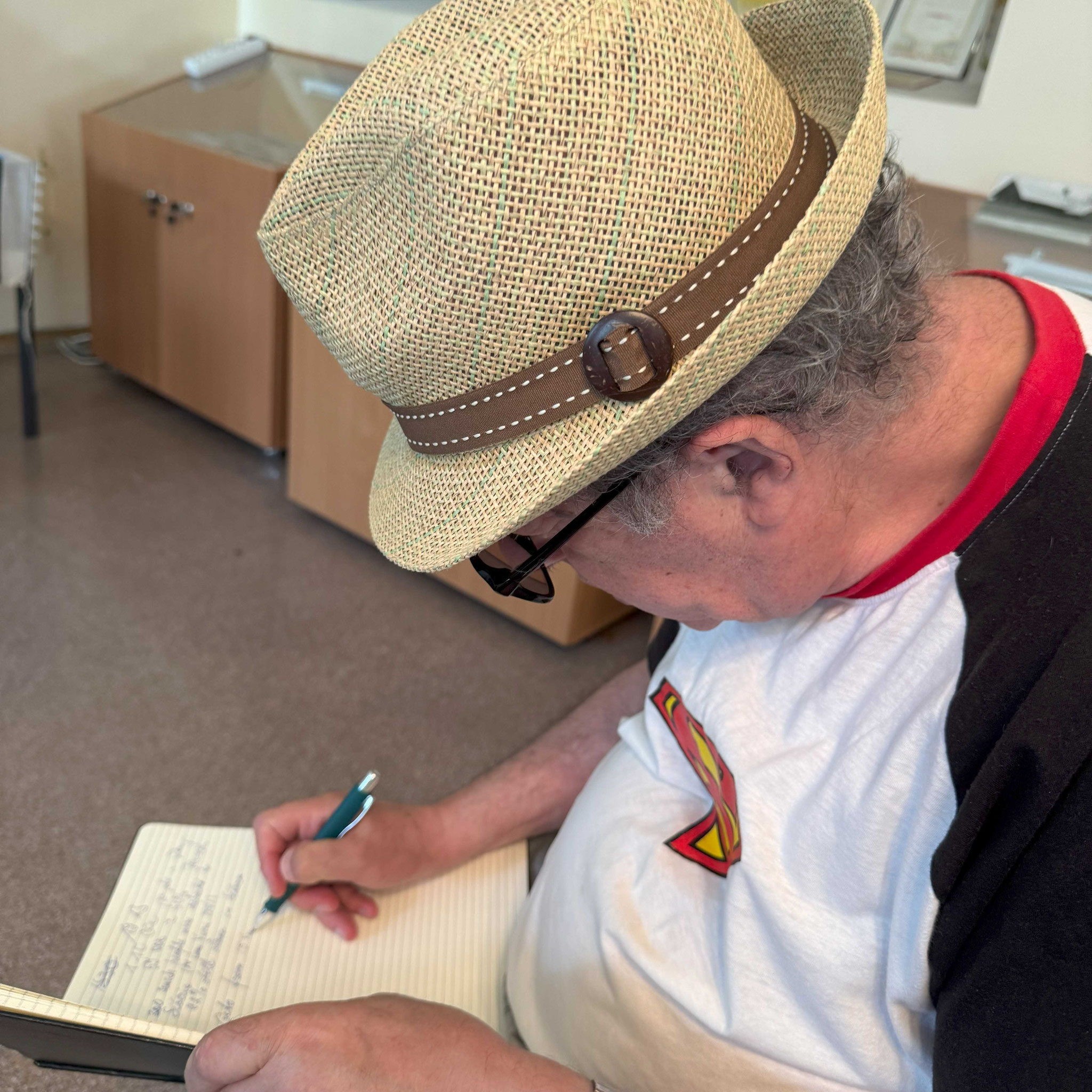

We arranged to meet on a Sunday morning in front of the synagogue. Josifs Ročko awaited me at the entrance gate to the grounds of the synagogue, built in 1850. He allowed almost no interruptions. He would either retort in a commanding tone, "Don't ask, the answer will come later," or state definitively, "I don't know." To me, that meant, "Don't ask any more questions." He only wanted to tell his story. When I reached for my pen to make notes in my pad, he would glare at me and say, "It's all in my book, which you'll get afterward." It was difficult for me not to jot down points, even if everything was already written. So, occasionally, I disregarded his instruction. Once, he took the pen from my hand and wrote bullet points and numbers in my notebook. Was he worried I would write something wrong? This was a completely new interview situation for me, but I couldn't bring myself to contradict him.

In the courtyard, he presented his exhibition on the history of Jews in Daugavpils. Depending on who ruled, the city had different names: Dinaburg, Dvinsk, and since 1920, Daugavpils. The first Jewish settlers arrived in the mid-17th century as refugees from western Ukraine and Belarus, coming to Latgale and Daugavpils. The Jewish community in Daugavpils grew continuously. In 1913, the city had 110,000 inhabitants, about half of whom were Jewish. He spoke of Jewish life in the city before the Holocaust, with a rich cultural scene, successful businesses, educational institutions, and 42 synagogues. He pointed to the many advertisements for theater, cabaret, or jazz concerts in the 1920s. He showed a postcard with French text. "We were a cosmopolitan city, comparable to Paris." These were all reproductions of exhibits he had collected.

The proportion of the Jewish population in the city decreased to just under 15 percent due to World War I, the October Revolution, and the subsequent Civil War. Many Jews had to leave their homes or fled this heavily contested border region. The Jewish communities in Daugavpils numbered only about 11,000 people, 80 percent fewer than before World War I.

At the beginning of World War II, more than 2,000 Jewish people managed to leave the city. They had to start new somewhere in the world as refugees. In June 1941, under Soviet rule, there were deportations of people to Siberia throughout the Baltics. Among them were 176 Jews from Daugavpils. A few days later, the German Wehrmacht reached the city on the Daugava River. This marked the beginning of the extermination of the Jewish population in Daugavpils in the shortest possible time. The first executions took place in the city itself. In July, Jews received an order to gather at a location outside the city. Approximately 13,500 people were rounded up in the Daugavpils Ghetto—Jews from the city and the entire region. Already by late July/early August, according to German reports, about 9,000 Jews had been shot. In November, another 1,000 to 3,000 people were shot. In December 1941, 962 Jews remained in the ghetto. After further executions, by May 1942, only 487 people remained out of the 13,500 Jews who had been forced into the ghetto less than ten months earlier. They were subjected to forced labor and some were taken to concentration camps. Fewer than 100 survived the ghetto. Some later returned to Daugavpils, among them Gersons Ročko, Josifs's father.

Today, about 150 people belong to the Jewish community. "About half are Jews. The other half are family members." On Shabbat, the weekly day of rest in Judaism, Josifs says about 10 to 15 men and 7 to 10 women come to pray in the synagogue. In the past, women sat on the first floor and followed the ceremony through small windows from above. The former women's section now houses the museum. Therefore, women in the synagogue sit behind a partition, shielded from the men's view. "I can concentrate better on God if I don't see women," says the family man. There is no rabbi in Daugavpils. "We have a 60-year-old man who lived in Israel for some years. He reads the prayers in Hebrew. But no one understands anything." He shows me a book with Hebrew text on the right page and text in Cyrillic script on the facing page. He explains that it's not a translation, but a transliteration of the Hebrew text into Cyrillic letters. "That way, Russian-speaking people can read the text," he explains, repeating, "But no one understands anything."

After the service, everyone gathers in the community room for a meal—the men at one table and the women at another. There's herring, bread, salad, and potatoes. "The salted herring symbolically represents the sweat and tears of the Israelite slaves in Egypt," Josifs explains. Along with that, there's vodka. When asked what was more important to him—the service or the subsequent gathering—he immediately replied, "Of course, the gathering with food and drink." But conversation is also important. "We all speak Russian."

More than 15 years ago, Josifs began to research the history of Jews in Daugavpils. He conducted research, gathered documents, photos, newspapers, calendars, books, and household items. The retired teacher built a museum that he now shows to people from all over the world. He has compiled the life stories of 150 Jewish individuals from Daugavpils. A significant person, for example, is Mark Rothko. He left the then-Dvinsk with his family in 1913 due to anti-Semitic pogroms in the Russian Empire. He lived in the USA and is considered a pioneering artist of Abstract Expressionism. His paintings are displayed in major museums worldwide. His family supported the comprehensive renovation of the Daugavpils Synagogue. Josifs points to a multilingual brass plaque that indicates this.

Josifs has published numerous books. In the city, he is known as a historian, local historian, founder, and director of the Jewish Museum. For his services, he received the "Order of the Three Stars" (Triju Zvaigžņu ordenis), Latvia's highest civilian state award.

He did not answer the question of whether his father spoke about his time in the ghetto. He answered why he built this museum and engages with the Jewish community with the words: "In memory of the Jewish people who lived here."