The Belarusian Cultural Center, nestled in a Vilnius Old Town courtyard, is more than just a meeting place. The Lithuanian capital has long been a significant refuge for people from Belarus, and as such, the center is deeply intertwined with the history of the Belarusian independence movement and its diaspora. Paulina Vitušcanka, a 32-year-old historian who is one of the manager of the center, embodies this connection.

Her parents came to Vilnius in the late 1980s to study. They were both activists who advocated for a sovereign Belarusian state. Born in Vilnius, Paulina grew up immersed in the Belarusian language and culture. Her heritage and her parent's stories shaped her. From them, she learned that the independence movement in Lithuania was much stronger than in Belarus, because the colonization by the Soviet Union was far more intense in her homeland. "This policy led to the identity of the Belarusian people being much more destroyed." While people in Lithuania already believed the end of the Soviet Union was near in the 1980s, people in Belarus were surprised by its collapse, Paulina recalls her father saying.

A History of Connection

As early as the beginning of the 20th century, Vilnius served as a place of exile for Belarusian intellectuals and activists. One of them was Ivan Ivanavič Luckievič, a leading figure in the independence movement. His extensive collection of archaeological and ethnographic artifacts, along with his library, led to the founding of the Belarusian Museum in Vilnius in 1921, which was named after him. However, with the Soviet occupation, the collection was dissolved, and the exhibits were scattered among various museums in Lithuania, Belarus, and even Moscow. The museum, an expression of Belarusian identity, ceased to exist.

It wasn't until 2001 that Belarusian activists in Vilnius began to revive the museum. The current collection is stored in archival boxes and on shelves in a small room at the cultural center, consisting mainly of photos and old documents. Paulina Vitušcanka, who is currently pursuing her doctorate at the University of Tartu (Estonia) on the topic of memory culture, feels connected to this history through her work at the museum and cultural center. A particularly moving exhibit for her is a piece of needlework that a Belarusian lawyer secretly made in a Siberian labor camp in the late 1940s. Paulina assumes she had to make and hide it in secret. "She probably unraveled every single thread individually from old textiles."

Paulina also tells the story of a museum exhibition that featured towels from two centuries. "It was about an everyday object that we use every day, but also about the everyday handling of our cultural heritage." Some towels were part of a dowry, some richly embroidered ones were gifts for special people, some were created as artworks for galleries, and some came from mass production. "Each item has its own story. This example is a great way to discuss the different ways of thinking about cultural heritage."

Support Services and Future Plans

Since the city of Vilnius made the building available to the organization in 2021, the cultural center has become an important meeting point and resource for people who feel connected to Belarusian culture. After the fraudulent presidential elections in 2020 and the subsequent mass protests, many people fled the Lukashenka regime to Vilnius. Paulina and her small team have made it their mission to help these people. However, she notes that the lives of the Belarusian diaspora vary greatly. Some came to Lithuania in the 1990s to study or work. They are now part of Lithuanian society and have decades of experience with democracy. However, they did not fight for freedom and democracy on the streets of Minsk with the risk of being sent to prison. The people who came to Vilnius in recent years because of the Lukashenka regime are often traumatized by their experiences. Paulina is also concerned about what happens to people who have to leave their homeland. As a child of a minority in Vilnius, she can imagine what many children are going through today.

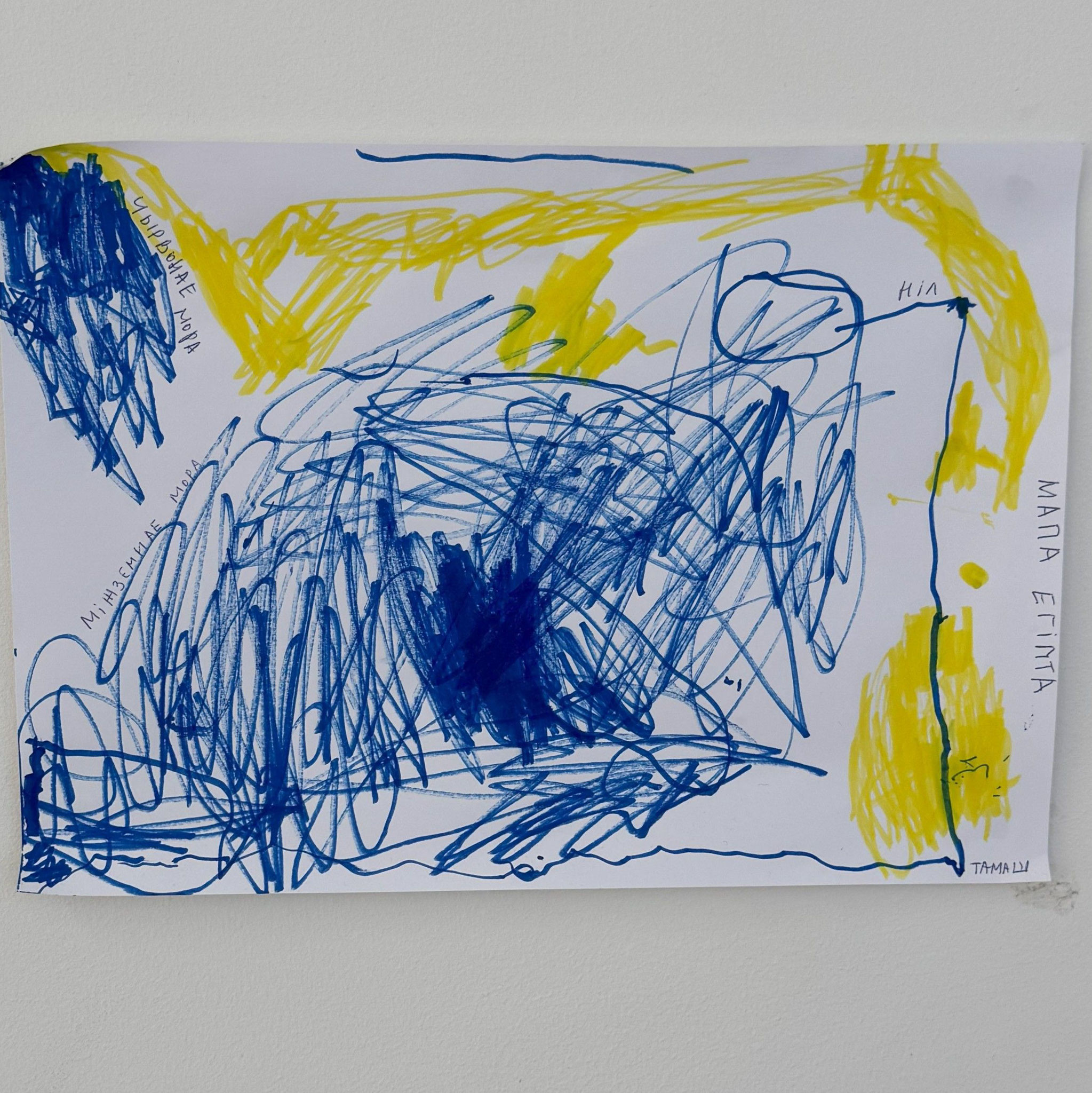

The cultural center offers a wide range of support, from Lithuanian integration language courses to programs that help children preserve their parents' Belarusian language and culture. There are also creative workshops, classes for Belarusian handicrafts, music, theater, exhibitions, and a library with Belarusian literature for children and adults.

The team also collaborates with the Ukrainian community to support refugees. "We also show our solidarity with the democracy movement in Belarus from here and support it as best as we can," says Paulina. Despite the numerous offerings and high demand, the center's future is uncertain. The city of Vilnius has only secured the premises until the end of the year. Paulina Vitušcanka does not know what will happen to the cultural center and the museum. "But this meeting place is so important for people from Belarus. We actually need even more opportunities to discuss our future and identity with the Belarusian community in Lithuania."