Lina Dikšaitė remembers playing in the dunes around Nida as a child. "We could roam the dunes without limits, even into the Kaliningrad region," says the current director of the Curonian Spit National Park.

The Curonian Spit is a narrow, crescent-shaped peninsula of sand dunes stretching almost 100 kilometers between the Baltic Sea and the Curonian Lagoon. This unique habitat, shaped by the interplay of sea, wind, and human influence, belongs partly to Lithuania and partly to Russia. The Russian part of the spit was declared a national park in 1987, and the Lithuanian part in 1991. Due to its special landscape and cultural significance, the Curonian Spit was designated a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site in 2000.

"For centuries, people viewed the sand as their enemy," says the head of the national park. Originally, the spit was a forested peninsula settled by fishermen. But in the 17th and 18th centuries, massive deforestation occurred after wood was discovered as an important raw material. Once the trees were gone, the sand masses became unstable and began to move in the form of wandering dunes. Entire villages and settlements were buried under the sand, forcing people to abandon their homes and resettle elsewhere.

It was not until the 19th century that people realized forests hold the sand in place and protect villages. Large reforestation projects were launched, in which the dunes were planted with pines to give them their current stability. "In a few places on the spit, we still have some of the old forest, a mixed forest with pines, spruce and some deciduous trees," Lina enthuses. The primary trees used for reforestation were various types of pine, as they are considered particularly robust and undemanding. To ensure the protective function of the dune landscape, controlled reforestation is also carried out at strategically important locations.

As the head of the national park, Lina Dikšaitė sees herself as an advocate for nature. Her main task is to mediate the conflicts of interest between protecting nature and cultural heritage on one hand and the demands of the popular holiday region on the other. Around one million people visit the Curonian Spit each year, which has about 5,000 inhabitants. Since tourism is the main source of income, Lina says, "we have to manage these tourist flows." For this reason, there are large, strictly protected areas that are off-limits to visitors. The border area with Russia is also mostly in the highest protection category and is a no-go zone. "These are requirements of the national park's management plan," Lina assures, "and have nothing to do with the current geopolitical situation or border security. Here there are no conflicts of interest, because it's also good for nature when people don't walk on the fragile sand dunes."

As an example of how the conflict between nature conservation and tourism can be solved, she cites the 50-kilometer-long bicycle path, which runs away from car traffic from the ferry terminal in the north to the Russian border. "Last year, this was completely renovated. A few kilometers run through a protected area of the highest category that is actually not allowed to be entered." The solution: A wooden fence on both sides of the path prevents cyclists from stopping and encourages them to ride through quickly.

The peninsula has so far been spared from resort complexes and has been able to maintain its typical character, as there have been strict restrictions on new constructions and renovations since the beginning of the 20th century. The peninsula can only be reached by ferry from Klaipėda or the Nemunas Delta. A few years ago, the regional airport in Nida reopened. Since then, small planes and helicopters have been able to land again in the middle of the national park. This has caused a lot of discussion among environmentalists. They fear that air traffic, with its noise and emissions, could disturb wildlife, especially birds in their resting areas.

"The goal is also to reduce car traffic on the island," says the nature conservation expert. "Although there is a lot of bicycle tourism, most people still arrive by car, even though the entrance fee to the national park is at an all-time high of 50 euros per car." She confirms that residents and people with second homes on the spit are exempt from this fee. "If we want to reduce car traffic, we have to further expand public transportation," says the connoisseur of the spit.

A vacation on the peninsula with its unique landscape is becoming increasingly popular, but at the same time, it is becoming a luxury that only certain groups can afford. Real estate prices on the Curonian Spit are among the highest in Lithuania. Wealthy people own holiday homes and have registered their second homes here. There are fewer and fewer hotels on the island, but more and more apartments. Locals sometimes rent out their houses or apartments during the summer months, while they themselves live in garages or other outbuildings during the season.

Lina Dikšaitė is pleased that the national park is launching a program in the fall that will allow school classes from all over Lithuania to go on field trips to the national park. "We received private donations that we can use to finance this. We have Nature School where people can get education programs and stay overnight."

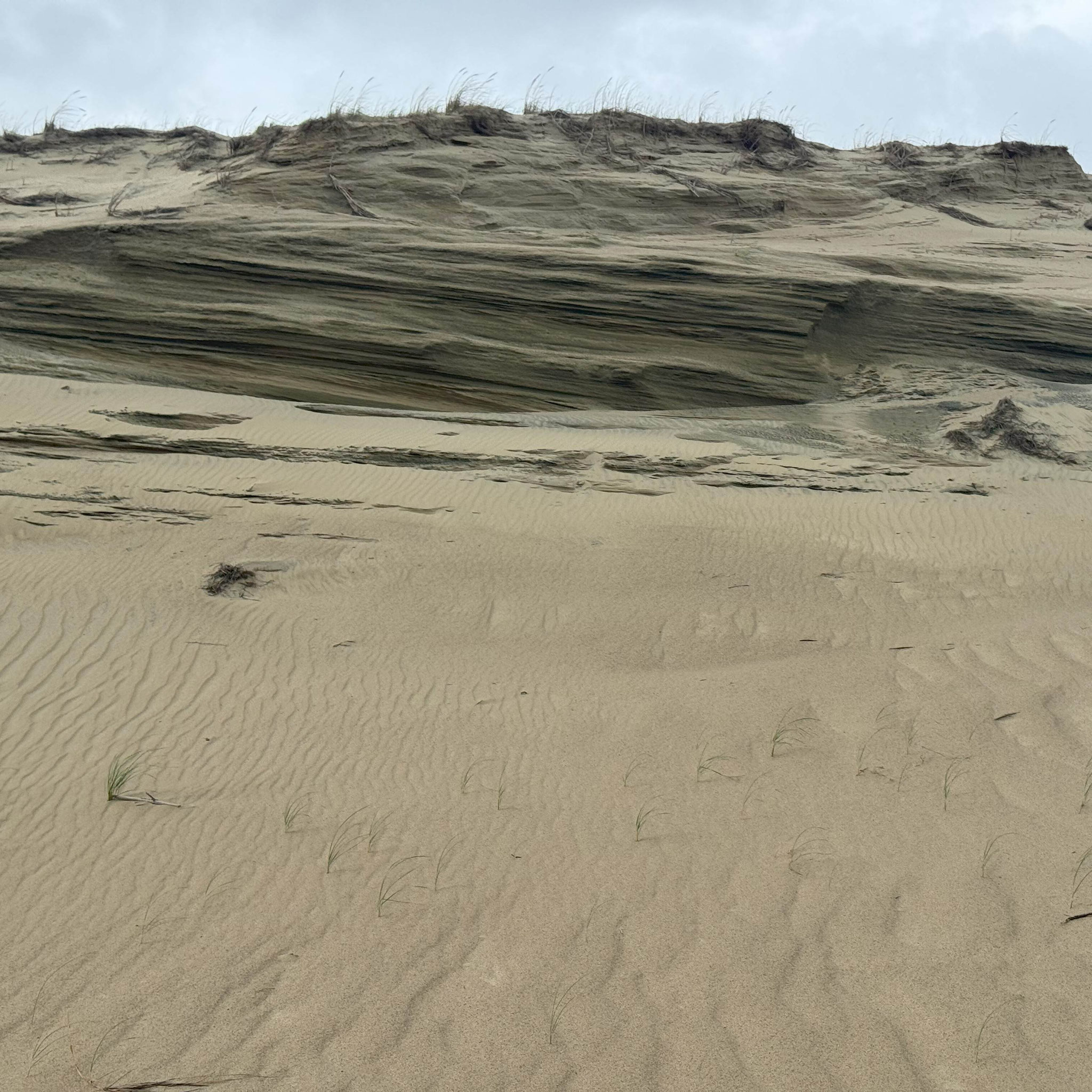

The Curonian Spit is a instructive example of how human actions can both destroy and restore nature. It shows how the vulnerability of nature is not only caused by natural forces but also by humans themselves, and can only be controlled through continuous human protection. "Here you can also experience different ecosystems like wetlands, forests, and dunes within the shortest distance," Lina promotes. She emphasizes that you can also get to know very different types of dunes here. Wandering dunes are large, bare sand areas that move with the wind. As the first barrier by the sea, the white dunes rise up. They are a type of wandering dune but are stabilized by pioneer plants like beach rye. Directly behind them are the grey dunes, which have a dense, stable covering of lichen, mosses, and plants such as heather. These fixed grey dunes are also referred to as dead dunes, a phenomenon especially visible on the Curonian Spit, where they once buried entire villages. The last type is the forested dunes, which are the most stable and protect the cultural landscape.

The entire Curonian Spit has held the title of "UNESCO World Cultural Heritage" since 2000. "We cooperated with the national park administration in the Kaliningrad region until February 24, 2022," Lina recalls. "That was also part of our duties as a cross-border world heritage site." There were some joint projects in research, environmental protection, education, and tourism. "At the moment, everyone is managing their own territory because there is no longer any dialogue," Lina explains. The director does not currently see the "UNESCO World Heritage" title as being in danger. "On the Lithuanian side, we continue to fulfill all the obligations associated with the title."