It's an imposing colossal structure of glass and rust-colored steel, standing right in the middle of the historic grounds of the former Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard. The striking museum is designed to resemble a ship's hull. Here, at the European Solidarność Centre (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności – ECS) in Gdańsk, the memory of the Polish trade union and its pivotal role in the collapse of communism in Europe is preserved.

Solidarność was the only independent mass trade union in the entire Eastern Bloc, whose existence the communist authorities were forced to officially recognize following nationwide mass protests and strikes by millions of workers.

With the Gdańsk Agreements in August 1980, Poland's communist government consented to the founding of independent trade unions. Lech Wałęsa, who worked as an electrician at the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard, became its chairman. Within a few months, the union grew to nearly ten million members. The success of this opposition workers' movement was a decisive step toward the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989/1990.

Grzegorz Piotrowski, a research specialist, emphasizes that the ECS is more than just a museum. "We want to look beyond the history of Solidarity and link it to current issues," says the sociologist and protest researcher. The ECS is the center for the memory of the peaceful movement for Polish democracy, freedom, and sovereignty, and simultaneously a place for contemplation and exchange that actively champions European values, democracy, and solidarity—values that are currently threatened by the Russian war in Ukraine.

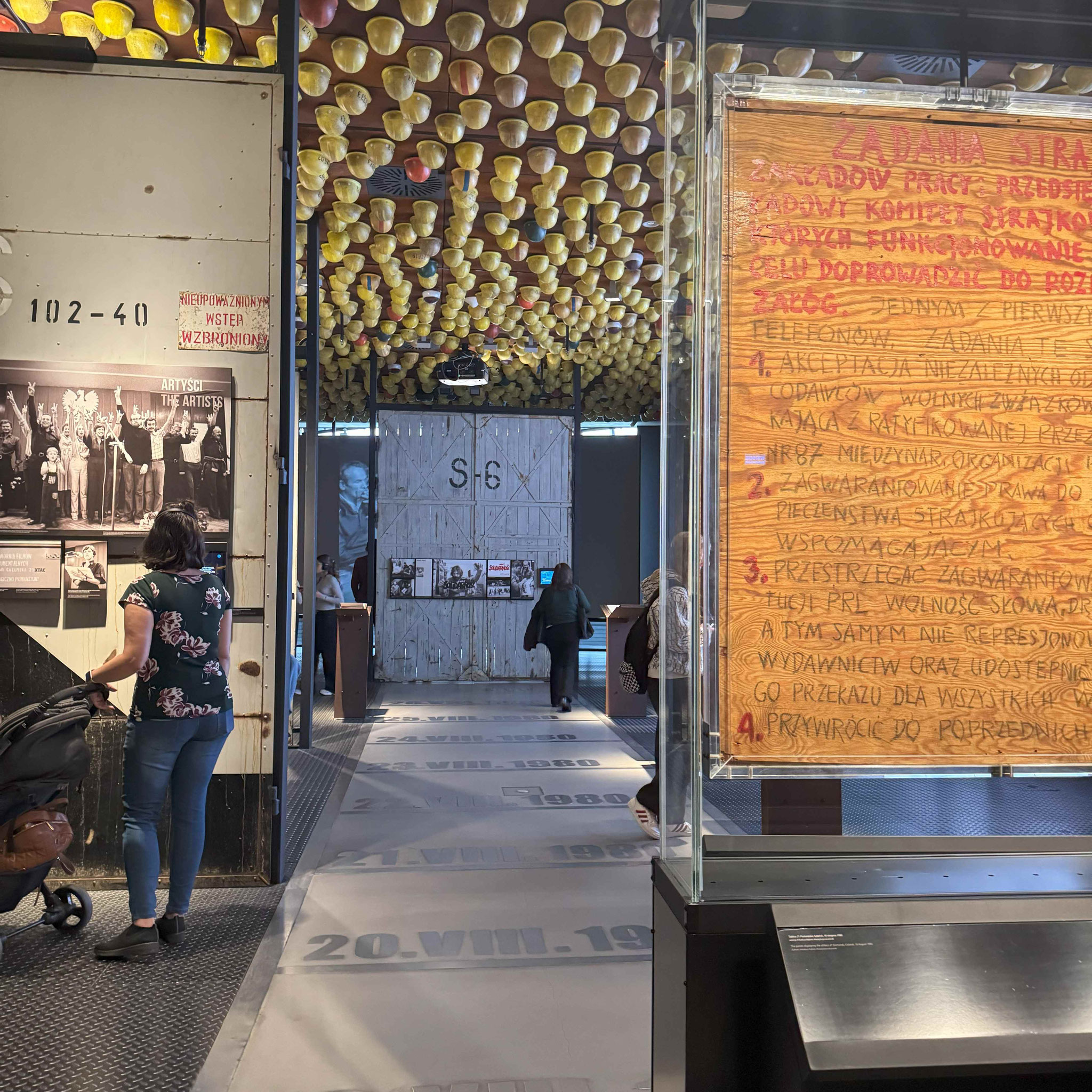

The 21 demands that the striking workers wrote by hand on two plywood boards and hung on the shipyard gate in 1980 were inscribed by UNESCO in the international "Memory of the World" register. The plywood boards form the center of the exhibition but also serve as a guiding principle for the work of the ECS. " Solidarność was concerned not only with economic and social demands but also with fundamental human rights," Piotrowski argues.

To convey and embody this message, the ECS serves as a public space where people can meet and engage in conversation. At the same time, it is a cultural center with a museum, a library, an educational center, and exhibition spaces. Various NGOs are headquartered here. "But even groups without fixed structures can utilize the infrastructure for their work."

The goal is to provide opportunities for people on the margins of society to become part of society. Piotrowski cites Polish courses for immigrants or special programs for people from Ukraine as examples, enabling them to actively integrate into Polish society. The ECS supports initiatives dealing with Ukrainian history and culture as well as the fight for freedom. "We also support Belarusian dissidents in their work. The peaceful protests in Belarus and the demand for freedom of opinion, speech, press, and publication link directly to the Solidarność protests."

Even though Polish society is highly divided, the researcher speaks of strong backing from Gdańsk's municipal community. "The city stands for freedom, human rights, and democracy. And that aligns with our mission."

Piotrowski explains that the ECS is independent in its operations. A large part of its funding comes from the city and the region. "However, the PiS government tried to cut the funding during its term." This was followed by a crowdfunding campaign. "It was so successful that we ended up having more money available for our work."

Piotrowski considers the strengthening of democracy throughout Europe to be a vital task. "We collaborate with various European organizations for this purpose." As a successful example of how the history of the Polish trade union can be linked with movements in other former Eastern Bloc countries, he mentions the current exhibition at the Hygiene Museum in Dresden, "Freiheit Svoboda Wolność." This also involves discussing what freedom actually is. And that brings him to the current debate in Poland. Poland was often occupied by foreign regimes. "Now, in free and independent Poland, there are voices on the right talking about Poland being governed by the EU and Brussels. But we can leave the EU anytime; we couldn't leave the Warsaw Pact," he points out, sharpening the contrast.

Part of the ECS's work is also about shaping the narrative surrounding the history of the Solidarność movement and the current political situation. "Everyone has their own narrative about the protest movement of the 1980s." That's understandable since this mass movement united very diverse social groups: not just workers, but also intellectuals, and religious and national groups. "This is why there are many different approaches to the topic, which offers a great deal of space for discussion." Many current leaders of various political parties originate from the Solidarność movement, resulting in different narratives and different conclusions for today's politics. "We want to counter this by telling the comprehensive story and providing historical context at this authentic site with the original documents and exhibits." Piotrowski sees it as a great advantage that people from various camps attend events and discussion rounds and talk with one another. "We are perceived as a cultural and political institution and a think tank for new ideas to carry forward the legacy of the Solidarność movement."

According to the scientist, it's hard to measure the exact influence the ECS has on strengthening democracy. However, 350,000 exhibition visitors and 800,000 people who visit the building annually demonstrate that the institution on the former Lenin Shipyard is an important voice in the current discussion about democracy and freedom in Poland, Europe, and globally. Lech Wałęsa, the electrician at the Lenin Shipyard and later President of Poland, monitors the developments very closely from his office on the ship hull's upper floor.