Approximately 20 million Poles—or people with Polish roots—live outside Poland, while around 38 million people currently reside within Polish territory. Migration is part of human history and is not a new phenomenon. Humans have always moved from one place to another in search of food, shelter, land, or better living conditions.

The emigration of millions of people is an inherent part of Polish history. The Emigration Museum in Gdynia is the first institution to tell this part of the Polish history. It's not just about facts and figures, but about the human stories, difficult decisions, big dreams, doubts, fears, and sometimes deep sorrow that lie behind every departure.

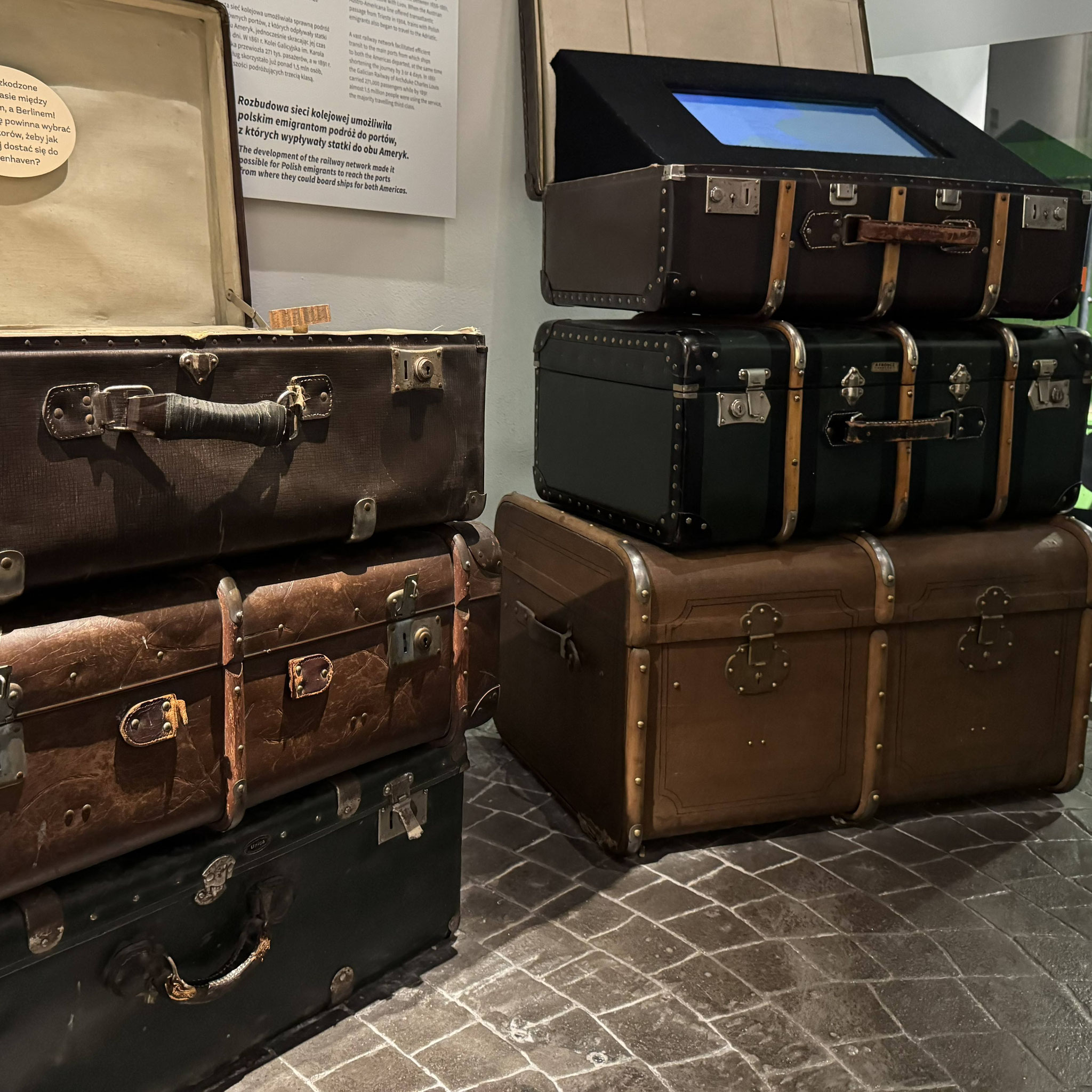

Łukasz Podlaszewski, the historian responsible for the museum's permanent exhibition, explains that the building itself is already part of the exhibit. The museum is located in the former Marine Station with the huge Transit Hall, a structure built in the Classical Modernism style with clean and functional lines. It was established in 1933 in the port of Gdynia. Thousands of Polish emigrants, who embarked on their journey to a new home from here on transatlantic ships, passed through these large halls and long corridors with their suitcases and belongings for processing.

The museum covers the history of emigration from Polish territories from the 19th century to the present day. It occurred in various waves – some were primarily politically motivated, while others were driven by economic hardship and hunger.

Mass migration in Poland did not stop with World War II. Due to the shifting of borders, millions of Poles found themselves outside the state territory. Resettlers, forced laborers, prisoners of war, and deportees faced the choice: return or stay.

The descending Iron Curtain drastically restricted legal emigration starting around 1949, as the communist leadership attempted to isolate people from the Western world. "Over two million people left Poland between 1949 and 1989," says Łukasz. Therefore, the Emigration Museum dedicates a separate chapter to the Cold War era.

"There were spectacular escapes for which people risked their lives; some even paid with their lives," the historian explains. "Most people left Poland during this time as tourists in travel groups." He recounts cases where drivers returned to Poland with empty coaches because all other travelers had absconded en route and requested asylum in the West. Łukasz points out that people in communist Poland first had to apply for a passport before they could travel.

Those who had no chance of getting a passport because they were already under surveillance by the Secret Service, were left with only a daring and life-threatening escape. Łukasz reports on the hijacking of Polish planes, where pilots were forced to land in Tempelhof (West Berlin) instead of Schönefeld (East Berlin). Others jumped from tourist boats off the coast of Scandinavia and swam ashore. There were also individual escapes by Polish military personnel who reached the Danish island of Bornholm in planes.

The Emigration Museum encourages people to tell their personal stories even decades later. Łukasz recounts meeting a man who had spent a year preparing for his escape hidden in the technical room of a freighter bound for Sweden. He remained undiscovered and arrived in Sweden. "People were very inventive in trying to flee the communist country."

With the start of the Solidarność movement and the imposition of martial law, emigration increased. On the one hand, passport issuance was liberalized, allowing people to leave on tourist visas, with many then staying abroad. At the same time, active Solidarność members were extorted into leaving under the threat of further repression. They were given a travel document that did not allow them to re-enter the country.

Even after the political change in 1989, many people left the country in search of work. "These different waves of emigration influence Polish society. Every family essentially has someone who lives abroad." Simultaneously, more non-Poles are living in the country. "The largest group of immigrants are Ukrainians – even before Russia's war of aggression." "These people are now in the same situation as Poles in Germany. For us Poles, it's an interesting process to observe how integration is taking place as hosts," says Łukasz. He notes that Poland is a very homogenous society without significant minorities. This, he suggests, may explain the fear of other cultures. The experience of many Poles in multi-ethnic societies, such as in England, is also having an effect in Poland. Integration is comparatively easy for Ukrainians because they are linguistically and culturally very close.

The diaspora of approximately 20 million Poles worldwide continues to influence Polish culture. Significant Polish literature was written outside Poland. Even the text of the Polish National Anthem was created in the 18th century in Italy when Poland had vanished from the map as a sovereign state. "There are many successful Poles abroad even today." In his opinion, the Polish state or Polish institutions utilize this potential far too little. "It doesn't have to be about persuading these people to return. There would be many other ways to cooperate." After centuries of emigration from Poland, more Poles are currently returning than leaving the country.